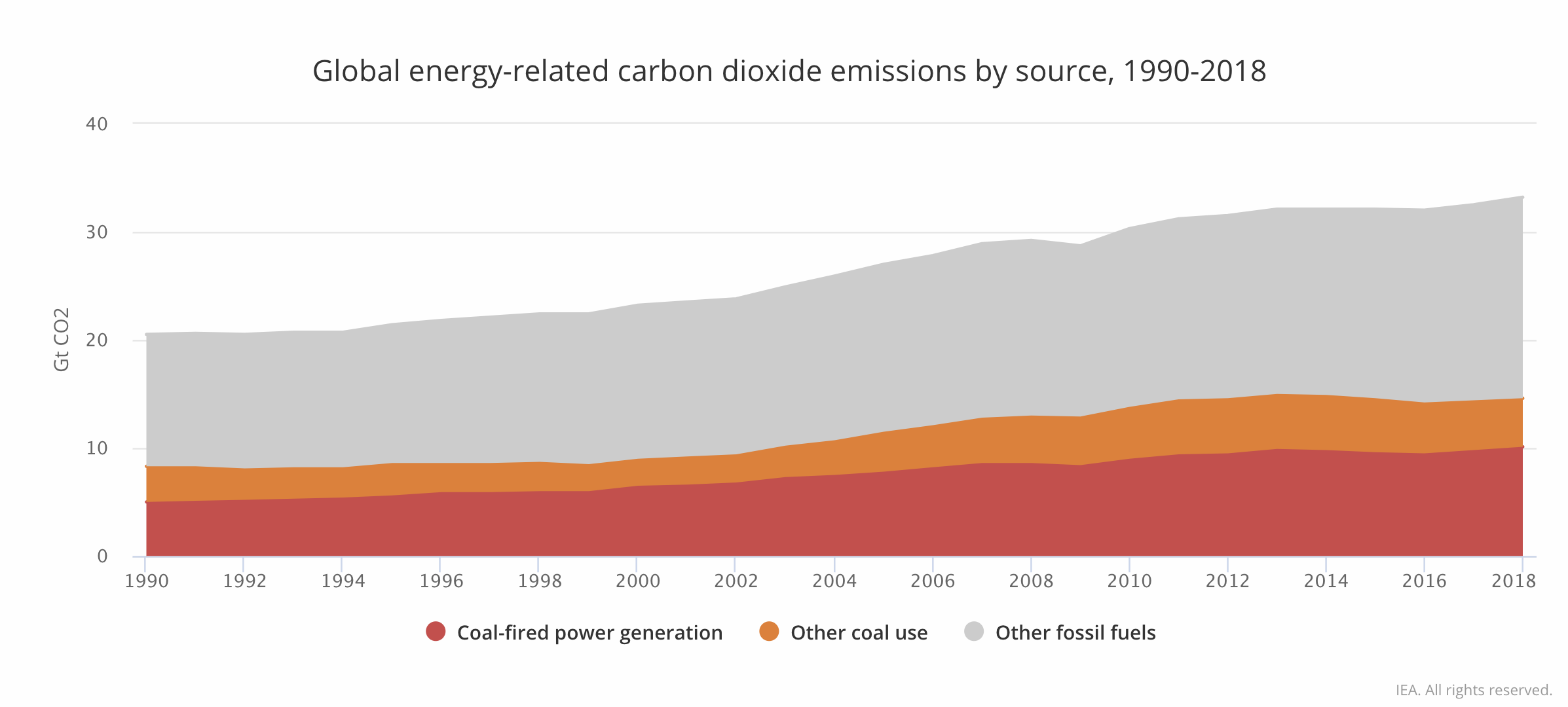

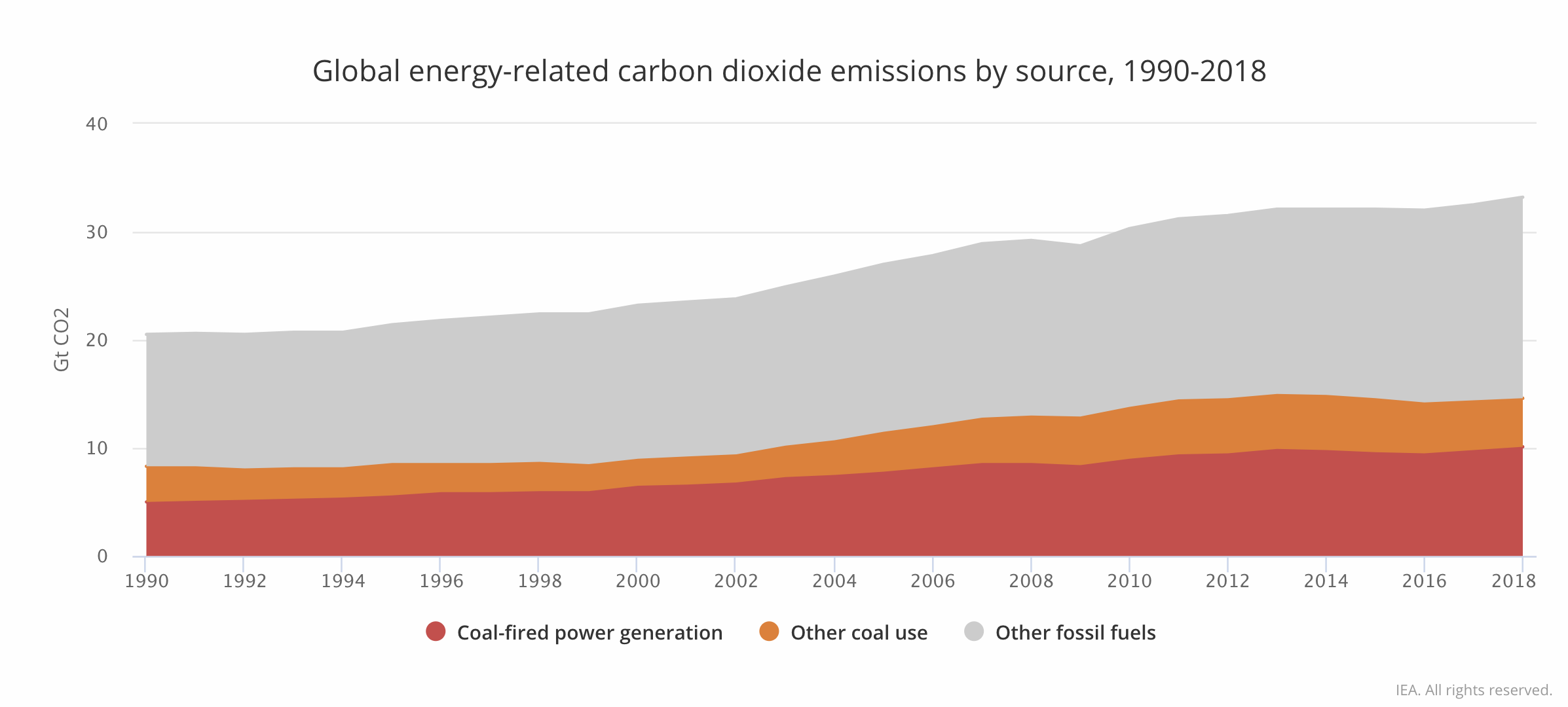

Driven by higher energy demand in 2018, global energy-related CO2 emissions rose 1.7% to a historic high of 33.1 Gt CO2, according to a newly released report from the International Energy Agency (IEA) annual Global Energy & CO2 Status Report. It was the highest rate of growth since 2013, and 70% higher than the average increase since 2010. Last year’s growth of 560 Mt was equivalent to the total emissions from international aviation.

While emissions from all fossil fuels increased, the power sector accounted for nearly two-thirds of emissions growth. Coal use in power alone surpassed 10 Gt CO2, mostly in Asia. China, India, and the United States accounted for 85% of the net increase in emissions, while emissions declined for Germany, Japan, Mexico, France, and the United Kingdom. The increase in emissions was driven by higher energy consumption resulting from a robust global economy, as well as from weather conditions in some parts of the world that led to increased energy demand for heating and cooling.

China saw the most substantial increase in energy demand, which grew 3.5% to 3 155 Mtoe, the highest since 2012. This accounted for a third of global growth. Demand expanded for all fuels, but with gas in the lead, replacing coal to meet heating needs and accounting for one third of growth. After three years of decline, energy demand in the United States rebounded in 2018, growing by 3.7%, or 80 Mtoe, nearly one-quarter of global growth. A hotter-than-average summer and colder-than-average winter were responsible for around half of the increase in gas demand in the United States, as gas needs grew both for electricity generation and for heating. India saw primary energy demand increase 4% or over 35 Mtoe, accounting for 11% of global growth, the third-largest share. Growth in India was led by coal (for power generation) and oil (for transport), the first and second biggest contributors to energy demand growth, respectively.

CO2 emissions stagnated between 2014 and 2016, even as the global economy continued to expand. This decoupling was primarily the result of strong energy efficiency improvements and low-carbon technology deployment, leading to a decline in coal demand. But the dynamics changed in 2017 and 2018. Higher economic growth was not met by higher energy productivity, lower-carbon options did not scale fast enough to meet the rise in demand.

The result was that CO2 emissions increased by nearly 0.5% for every 1% gain in global economic output compared with an increase of 0.3% on average since 2010. Renewables and nuclear energy have nonetheless made an impact, with emissions growing 25% slower than energy demand in 2018.

Increased use of renewables in 2018 avoid 215 Mt of emissions, the vast majority of which is due to the transition to renewables in the power sector. The savings from renewables was led by China and Europe, together contributing two-thirds to the global total. Increased generation from nuclear power plants also reduced emissions, averting nearly 60 Mt of CO2 emissions. Overall, without the transition to low-carbon sources of energy in 2018, emissions growth would have been 50% higher.

Energy efficiency was the largest brake on emissions growth in 2018, but its contribution was around 40% lower than in 2017, largely because of a continued slowdown in implementing energy efficiency policies.

For the first time in almost a decade, 2018 saw an increase in plans to develop large-scale carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS) facilities. By the end of 2018, the number of projects operating, under construction, or under serious consideration increased to 43. China is operating a new facility to capture CO2 from natural gas processing for use in enhanced oil recovery, and, in Europe, five new projects are under development.

The new facilities have the potential to capture up to 13 Mt CO2 annually, a 15% increase in potential CO2 capture across the global project pipeline.